Indigenous fire management: Lessons and challenges for constructing new fire management paradigms with an intercultural vision

In October’s edition of the PyroLife Webinars, we were joined by Professor Bibiana Bilbao, from the Environmental Studies Department at Universidad Simón Bolivar, Venezuela.

We are privileged in PyroLife to have listened to Indigenous fire management approaches from First Nations and Australian Aboriginal perspectives, and there is an endless diversity of Indigenous knowledges and geographies. Bibiana illustrated a case of Indigenous fire management in South America with Pemón communities in Venezuela, sharing lessons and challenges for constructing a new fire management paradigm with an intercultural vision. Effective, culturally just and sensitive measures for participatory and intercultural governance are key to current and future fire management.

Bibiana started by sharing how indigenous-managed territories are often the most effective in reducing carbon emissions. There’s a strong link between indigenous land management and environmental protection, higher biodiversity, reduced deforestation, and reduced GHG emissions.

In tropical areas, fire can help enrich nutrient-poor soils, and create patches of light for certain species to thrive in a more varied forest composition. However, today there’s also an increase in the number and severity of fires, even in protected areas.

As such, a new fire governance is needed. We need to ask: how can fire be managed in coexistence with communities who rely on forest resources?

For this, we zoom in on Canaima National Park, Venezuela. It’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Guayana, a 3000 million year old territory, where Pemón indigenous populations continue living here for generations (in a very uplifting fact, Indigenous populations are increasing here). However, as a nature preserve, fire use was completely suppressed in Canaima since the 1980s (sound familiar?), even though Pemón have been using fire since time immemorial to manage the landscape. This controlled fire promotes the fertilization of soils and the growth of certain species and crops (in specialized systems called conucos), and has important implications for hunting and even fishing in the forest-savanna-river edge systems. Further, their fires increase soil pH (in very acidic soils) and reduce aluminum toxicity.

Back in 1999, Bibiana was invited to study fire impacts on the vegetation in Canaima in order to increase the effectiveness of fire management. Her team conducted 31 experimental fires. She said that as scientists, they were able to set up plots, but the Pemón people knew the best moment and strategy to light fires, so they were invited to help. These experiments were conducted in different years in different seasons to acquire diverse results.

The 3 most important results from these experiments were:

- We can have different fire histories, different biomass accumulations in different plots with different treatments all at the same time. There is great heterogeneity of biomass accumulation.

- A necessary minimum of biomass is needed for fire to spread: 600g per square meter to be exact.

- The years without fire (under fire exclusion policy) showed a higher accumulation of biomass. The proportion of dead biomass increased in proportion to the years after the last burn.

What does all this mean? The policy of fire exclusion was increasing a dead fuel load, exposing the system to higher intensity fires! …Again, sound familiar? The researchers found that savanna vegetation could support the creation of mosaic patches with different fire histories, in a technique that imitates ancient practices employed by the Pemón people through cooperative burning, in order to stop the advance of high intensity fires.

This marks a turning point, where scientific knowledge helped support ancestral knowledge (rather than substitute or suppress it), for a more integral fire management approach. A change in policy was clearly needed.

And yet, Indigenous people feel they are losing their cultural knowledge of fire. The elders are the holders of this knowledge, but as an oral transmission system this knowledge is getting lost between generations, especially as kids are taken to bilingual schools far from their communities.

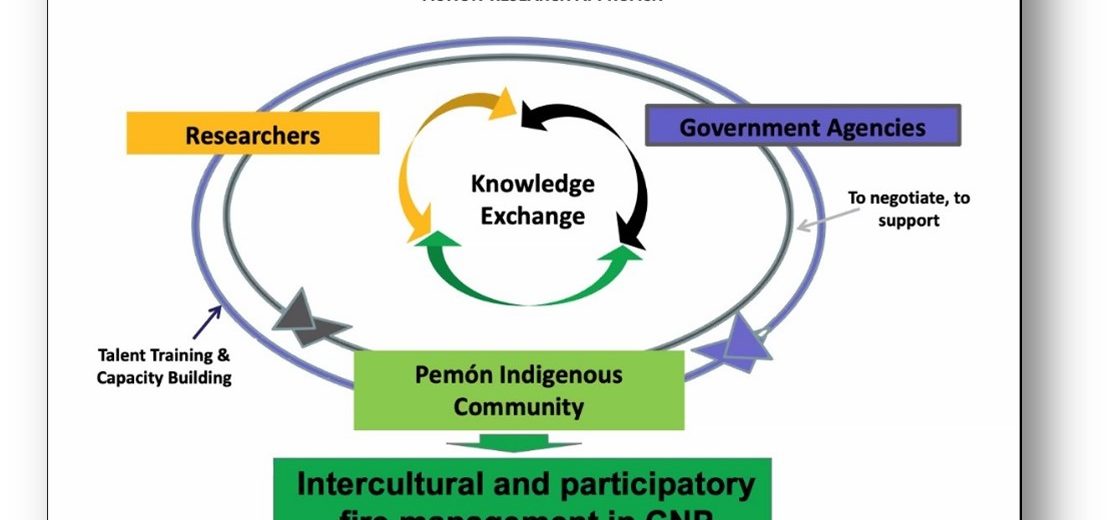

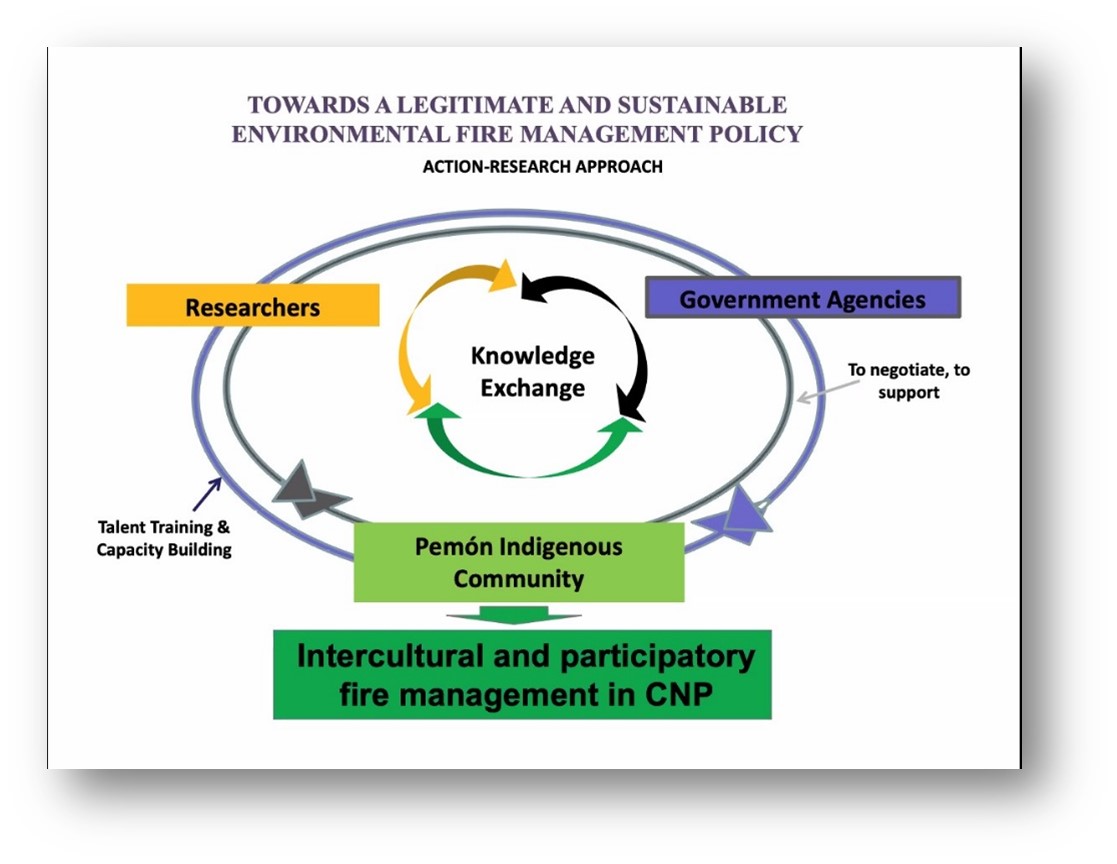

On a hopeful note, young indigenous researchers were promoted within Bibiana’s projects to conduct interviews with grandparents and catalog this knowledge in a book. And now there are more than 20 active projects in the region with Indigenous participation! The force generated by this action-research approach fosters a more legitimate and sustainable environmental fire management policy.

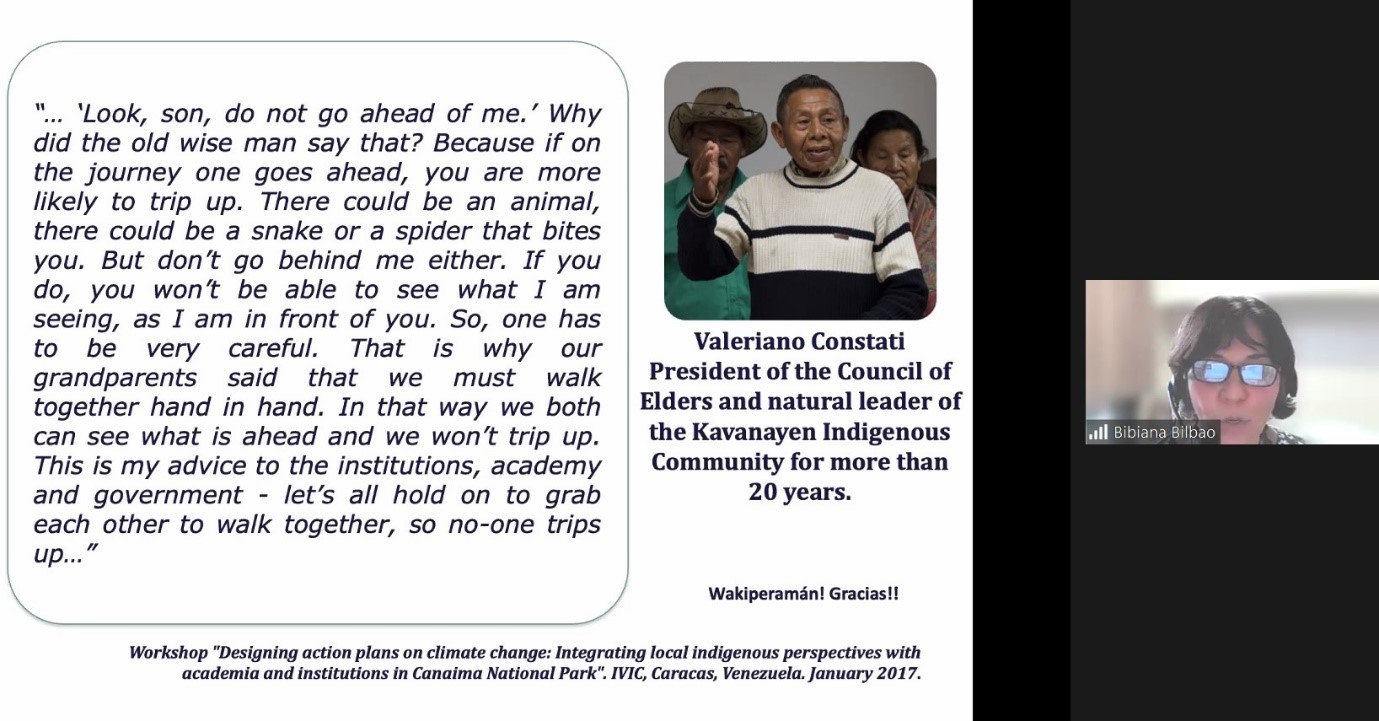

While there is still a long way to go, these projects have advanced dialogues between indigenous communities, institutions and scientists. This essentially fosters the respect of Indigenous knowledge, creates greater confidence and trust in institutions, creates legitimate commitments by institutions to include Indigenous knowledge in fire management, and sows the seeds to cultivate a paradigm shift in fire management. A national law is on its way to encompass these processes and learnings, and a Participatory and Intercultural Fire Management Network has begun between 60 different Indigenous peoples and institutions in Guyana, Brazil and Venezuela to create an empowering paradigm for Indigenous communities to actively participate in decision-making for fire management in their territories.

PyroLife researcher and webinar moderator Isabeau Ottolini gathered some great questions from audience members, to which Bibiana provided some further reflections: this experience has changed her own paradigm as an academic- she learned more through this project than any academic formation. Also, aside from publishing scientific studies, participatory video techniques were crucial to promote this knowledge in order to be more accessible and impactful to other indigenous communities aiming to adapt to climate change. The role of science is we have the responsibility to translate the message of social-ecological problems, to quantify and qualify the benefit of this kind of management to the people that make decisions, though we risk over-simplifying the problem. This is why local communities must be included in the implementation of new policies, it’s the only solution! One of the most important roles we can have is to recognize the harms of colonialism and create knowledge interfaces in a more horizontal and trusting way, where every type of knowledge is useful and valuable. It’s a conflictive situation but we have a duty to engage. Further, there are many kinds of indigenous knowledge: ancient, adaptive, and new. It is changing and evolving, so we need to create a rich atmosphere that is participatory, to not only “learn from” Indigenous people but include them in decision processes.

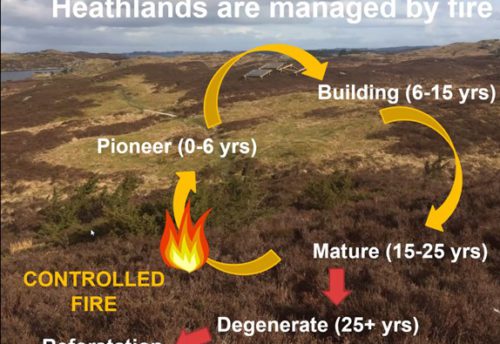

Finally, PyroLife is situated in Europe. As such, it is important to better integrate local knowledges from abandoned rural areas here before they disappear. The absence of local communities seems to be one of the main causes of large wildfires, and there’s a resurgence in recognizing local knowledge (ie. pastoralist and agricultural knowledge) as critical. Rural Europe, though, faces large problems in the fragmentation of territories with different (often absent) owners. One solution could be fostering agreements between owners for common fire management on the scale of watersheds or “firesheds”, in all their beautiful heterogeneity. Two things are certain: there is much to give hope and much to be done!

Leave a Reply