All over the world, Indigenous Peoples use fire to manage their surroundings in sustainable ways. Through their profound expertise and knowledge, these fire stewards know exactly when, where, how and how long to burn, thereby carefully protecting, supporting, and nourishing their environments. If we want to learn what Living with Fire really is, we need to listen to the Indigenous Peoples and learn, in respectful and ethical ways, from their vast knowledges and experiences.

That is why we kicked off the first of the PyroLife webinars series with the key topic of Indigenous Fire Management, together with three Indigenous researchers: Simon Lambert – member of the Tuhoe and Ngāti Ruapani tribes, Aotearoa-New Zealand; Amy Christianson – a Métis woman from the Cardinal/Laboucane families of Treaty 6/8 territory; and Brady Highway – from the Asinīskāwitiniwak, the people of the rock.

What are Indigenous Knowledges and why do they matter?

As Amy Christianson explains, there are different ways of creating knowledge. One way is the European/ Western approach, based on human dominance over nature and considering the scientific method – carried out by certain ‘experts’ – as the only valid way to generate knowledge.

And then there is Indigenous Knowledge, or rather ‘knowledges’ as there are as many Indigenous Knowledges as there are Indigenous Peoples. These are based upon long-term observations, grounded with peoples’ local relationships with the land. Such knowledges are handed down from generation to generation, with new knowledge continuously being generated and incorporated. Importantly, Indigenous world views do not see land, water, fire, and ecosystems as external to humankind (as is common in the Western worldview), but rather that we are all complexly interconnected.

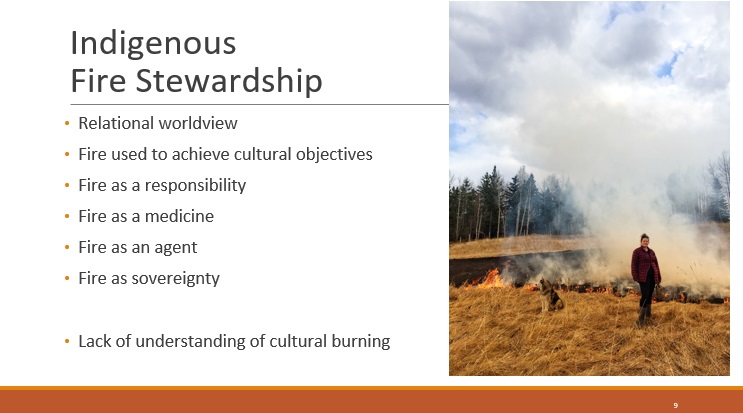

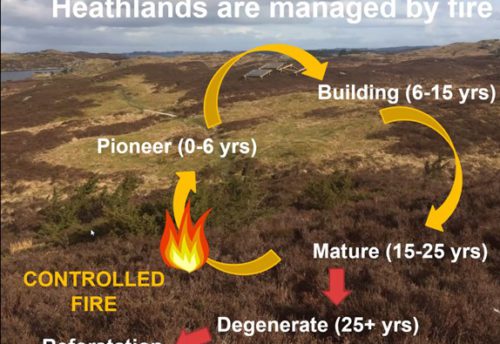

All around the globe, Indigenous Peoples use fire to sustainably manage, support and nourish their environments, for various cultural and ecological aims. Based on their intimate relationships with the surroundings, the fire stewards have vast in-depth expertise and knowledge. They know exactly when, where, how and how long to burn, by observing the weather, the ecological conditions, and the topography. Just to put some examples, berry bushes are burnt without affecting the roots, so that the plant survives and provides plentiful berries. Smoke near rivers decreases the water temperature and aids fish spawning. And changing snowlines throughout the seasons are used to limit the fire to specific areas. Moreover, for many people cultural burns are a family activity; a chance to spend time together and hand down knowledge from one generation to another. In this sense, Amy Christianson and Simon Lambert talk about the relational worldview which is deeply embedded within Indigenous Fire Stewardship. Fire is a living entity (just like you and me) and its use comes with a sense of responsibility towards the landscape and our relations with it. Through fire, people’s connection with the landscape are reasserted, healthy ecosystems are created, and it is good for the land and the people.

Indigenous knowledges and fire: from suppression to inclusion

For a long time, Indigenous fire knowledges and practices have been ignored and suppressed. Just look at the history of North America. With the continent’s colonization and the European obsession to protect timber and water resources, colonizers prohibited burning practices. By taking fire out of the landscape, forests increased while more fire-resilient landscapes with grasslands decreased (see the change in Canada’s landscapes in this photographic project, The Mountain Legacy).

This cultural severance – the loss of Indigenous Fire Stewardship, and associated loss of fire knowledges, traditions, and identities – greatly impacted Indigenous Peoples. At risk of being imprisoned, fined, forced to fight fires, or even lose their lives, they could no longer carry out their role as fire stewards. Even so, many Indigenous Peoples continued – in the background – with the burning practices, but never again at the scale it used to be. As such, the changing landscape is increasingly seeing more ‘bad fires’, i.e., fires that burn so intensely that they destroy the environment and make it impossible to live from the land.

Fortunately, Simon Lambert tells us that a shift is taking place to once again value and celebrate Indigenous knowledges on fire. Firstly, there is an increasing understanding that disasters are intrinsically social, whereby the Western unsustainable modes of living cascade into hazardous disaster landscapes.

Secondly, Western research is finally starting to acknowledge that Indigenous Peoples know what they are doing and are greatly experienced to manage their territories. This in stark contrast to decades of aggressive fire suppression, which have increased wildfire risk (see this article by Parisien et al, 2020).

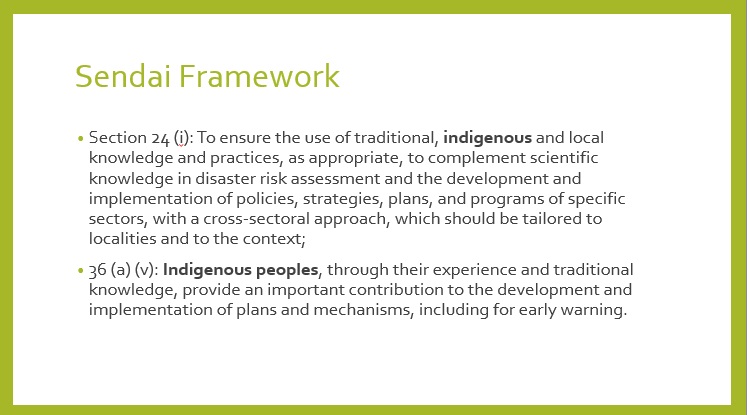

Thirdly, Indigenous Peoples are often at the frontline for fighting for the planet’s future, and treaties and multilateral agreements are increasingly acknowledging their right to sovereignty and managing their surroundings (e.g., through fire). For instance, the Sendai Disaster Risk Reduction Framework specifically acknowledges the importance of Indigenous knowledges and sovereignty:

Inspiring projects: Blazing the trail and Indigenous Guardians

Fostering Indigenous Fire Knowledges and Stewardship, here are two inspiring projects:

Blazing the trail is the first Indigenous-created product for FireSmart Canada. This booklet, full of artwork from Indigenous artists, collects the stories from 11 different Indigenous Peoples and communities. It celebrates and shares stories on Indigenous fire stewardship and leadership, acknowledging their key role in fire mitigation and prevention.

Indigenous Guardians. On behalf of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, Brady Highway is working on a national strategy to make it possible for Indigenous Guardians to recover stewardship over their traditional lands. Specifically related to fire, Brady is working on three different pilots:

- Before the Fire: This first pilot aims at developing people’s transferable skills and experiences, through involvement of community-scale projects like FireSmart. For this, key activities are research, education, and providing economic opportunities for the Guardians.

- During the Fire: Oftentimes no fire training is available for First Nation people, and many jobs related to fire incidents are given to non-indigenous people. As training and capacity building are essential, this second pilot aims at giving Indigenous Guardians the necessary training and hands-on experience with working with fire.

- After the Fire: This third pilot creates partnerships for Indigenous Guardians in fire management and stewardship. It includes activities like management planning (e.g. estimating which values are at risk or modeling forest fuels) and career development opportunities for the Guardians.

To conclude

Indigenous Peoples have the right to manage the environments, and they have the knowledge(s) to do so sustainably. However, a real challenge is preserving, protecting, and transmitting such knowledges. Another challenge is the speed at which the global environment is changing. To face these challenges, collaboration with other knowledge keepers, including scientists, is necessary. However, considering a long history of Indigenous knowledges being excluded, suppressed, and appropriated by Europeans/westerners, such collaboration needs to be built upon ethical engagement, respectful relationships, informed consent, and sovereignty over data.

You can watch back the webinar right here:

Leave a Reply