By Simona Dossi

Identifying gaps, challenges and opportunities towards integrated risk management

This was the first Europe-focused “Living with Fire” webinar; during which wildfire and flood risk in the Mediterranean were explored by discussing the gaps, challenges and opportunities towards an integrated risk management. Three presenters shared their expertise from Mediterranean risk management: Eduard Plan and Marta Giambellia are risk management professionals based in Spain and Italy respectively, and Bàrbara Ortuño is the mayor of the El Bruc municipality in Catalonia. Plana started the webinar by presenting a conceptual overview of wildfire risk management, Ortuño followed by sharing her municipality’s experience in the Life Montserrat European project, and Giambelli closed by presenting a case study illustrating a participatory risk management approach developed at CIMA.

Eduard Plana, head of the Forest Policy and Risk Governance department in Forest Science and Technology Centre of Catalonia, provided a valuable perspective from working for a research institution that works closely with stakeholders. Plana started by defining integrated wildfire risk management as an “amazing challenge.” Although wildfires are a natural hazard, Plana characterised them as the most social-natural hazards because the combination of natural and anthropogenic factors of wildfires are extremely cross-linked. Wildfire impact is strongly associated with the exposure and vulnerability of housing and infrastructures. Furthermore, especially in the Mediterranean, the recreational and touristic use of forested regions brings large numbers of, often uninformed, people to high-risk regions.

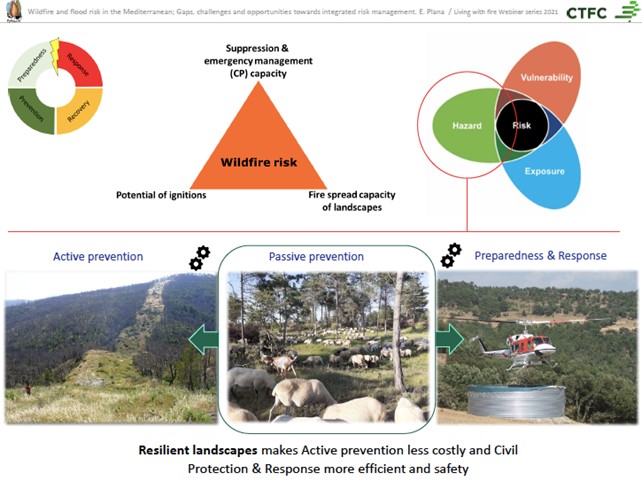

Figure 1: Eduard Plana presentation slide illustrating his summary of three factors contributing to wildfire risk and the impacts of passive wildfire risk prevention actions.

The wildfire hazard itself, can be controlled through the spatial distribution of fuel through land management. This is a particular difference between wildfires and other natural hazards; it is difficult to control rainfall or snowfall but “we can influence perfectly” the level of wildfire hazard, explained Plana. Through land management methods (e.g.: traditional landscaping, prescribed burning), passive prevention allows the landscape and the community to increase its preparedness and response capacity, while decreasing the need for active prevention methods (e.g: creating fire breaks). There are two processes, however, influencing wildfire hazard: land use changes and climate change; these parallel processes are uncertain and complex, providing a huge challenge to reduce wildfire hazard. Plana summarises the three main factors influencing wildfire risk as: (1) suppression and emergency management capacity, (2) ignitions potentials, and (3) landscape fire spread capacity; this is illustrated with the diagram in figure 1.

Plana reminds us that it is known, and well documented scientifically, that fire is a natural component of ecosystems. There are fire adapted ecosystems both to low intensity, high recurrence fire, and to high intensity, low recurrence fire. There is good fire that helps prevent bad fire. This truth, however, is not always clearly understood among wildfire stakeholders. “There is not always a clear distinction between fire and wildfires [although] everyone has a clear distinction between snow and avalanches, and even between water and floods.” Plana adds, that it is important to wonder if we are able to restore such fire-adapted landscapes. From his experience, the ideally fire-adapted forest landscapes are different from the forest owners preferred landscapes (e.g.: in terms of productive provisions). This difference poses a challenge in how to optimise different ecosystem objectives.

What does living with fire mean, and how can we plan it?

Although the fire community is approaching a consensus that it is possible, and necessary, to live with fire, there is a need to clarify what this means exactly; this is relatable to the challenge of communicating the concepts of living with floods. Plana suggests that there is a responsibility and a need to effectively communicate and explain why and how living with floods and fire is important. Wildfire management, according to Plana, is more complex compared to flood management, as suppression is closely related to wildfire hazard; wildfire hazard is therefore not only a spatial planning challenge but involves a larger number of stakeholders and processes. Although there is a European Commission commitment to achieve landscape fire resilience, it is important to clarify exactly what this means for society. Currently, the main solution adopted is to suppress all kinds of fire; this approach paradoxically increases the risk of future fires by allowing fuel load accumulation. More clarity, communication, and collaboration are needed. In comparison to floods, which are predictable in terms of the area they impact, wildfires are a more random and transient phenomenon; this poses further challenges in how to convince spatial planners to take actions in their regions. No unique solution is feasible for wildfire management, and solutions need to be tailored to specific regional and stakeholder needs and objectives.

Dealing with fire mitigation, who pays for what to whom?

An important consideration for this question is what is exposed to wildfire hazard, and to what extent is it vulnerable to the hazard. Plana used the example of creating firebreaks around residential areas near the wildland to illustrate that in the Mediterranean there are mostly reactive legal risk reductions measures. Communities are legally asked to create firebreaks, while knowing that fire spotting can allow intense wildfires jump those barriers easily. To truly reduce the risk in these wildland-urban interface communities, it is necessary to look beyond the wildland borders and take a holistic approach which connects the wildlands and the communities; this will enable to better reduce the impact potential of high intensity fires.

What to communicate and how to involve the fire community?

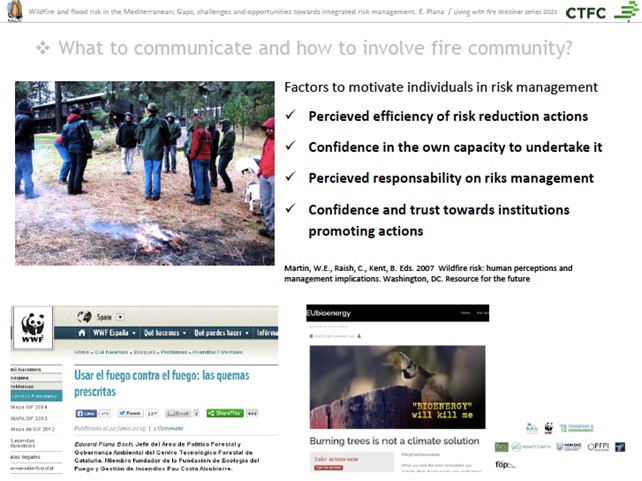

Plana expressed that the fire community should include all the actors: both those providing wildfire protection and those receiving it. The factors which motivate these actors to get involved in risk management are summarised in his slide in figure 2. Lastly, Plana discussed the ownership of risk and poses an important question “Should we ask people to be prepared [for wildfires], or should we ensure through spatial planning to not put people in danger?”

Figure 2: Eduard Plana presentation slide supporting his reflection on how to communicate to and involve the fire community, including the relevant factors motivating human action in risk management.

Bàrbara Ortuño is the mayor of the El Bruc municipality, a small rural municipality in Catalonia, Spain; this municipality includes large, forested areas. El Bruc experienced first-hand the increasing wildfire risk caused by land abandonment and poor forest management, and experienced two large wildfires in the last 40 years. Ortuño shared El Bruc’s experience and involvement in the Life Montserrat project, a European Life project for biodiversity, which spanned between 2014 and 2019. The primary lesson from this project is that building a diverse landscape with open spaces and pastures helps maintain biodiversity while also reducing and mitigating wildfire risk. In the Mediterranean region, it is well known that there is a lack of proper forest management. The widespread land use changes related to land abandonment and increased timber production have cause an increase in landscape continuity and forest density throughout the Mediterranean. The Life Montserrat project aimed to improve fire prevention and biodiversity through creating a green infrastructure through forest restoration, creation of open areas, and implementation of small farms for grazing activities. Key strategic areas to focus on were identified by firemen to serve the entire region effectively. Experts have concluded that the objectives of increasing fire prevention, biodiversity, landscape resilience, livestock activity, and stakeholder engagement have been achieved. Ortuño believes one of the most important outputs of the Life Montserrat project was the creation and reinforcement of a strong social ecosystem. This ecosystem includes many actors working together on the field including residents, private associations, and non-profit organisations. The project also created a lot of scientific data which helped advance understanding of wildfire prevention and land management. Ortuño highlighted the importance of supporting and incentivising small farms, allowing people to make a living from this work, in order to prevent land abandonment and in turn support wildfire prevention.

Marta Giambelli is an expert in civil protection planning and procedures for floods risk at the CIMA Reaserch Foundation, a non-profit research foundation active in disaster risk management and civil protection. Giambelli presentation focused on integrated and community-based disaster flood risk management and shared the necessary steps toward a community-based disaster risk management. Flood risk, like wildfire risk, is influenced from development processes (such as urbanisation and land use) and can be further exasperated due to climate change. These processes are causing pluvial and flash floods to become more frequent throughout Europe. The interconnectedness between the causing processes leads to the need for disaster risk reduction strategies which integrate various disciplines and apply multisectoral risk assessment and decision making. Disaster risk reduction measures should systematically reduce existing risk and avoid creating new risks by reducing vulnerabilities and strengthening communities and systems. Giambelli highlighted, as did the other speakers, the critical importance of successful engagement and involvement of local communities and stakeholders.

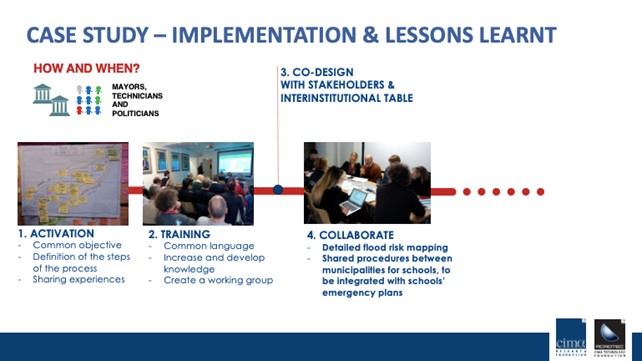

Figure 3: Marta Giambelli presentation slide summarising the stages of the participatory process case study implemented by CIMA in Val Polcevera, Italy.

Giambelli shared the experience CIMA has had in flood preparedness planning at the local, municipal level in the Italian context by presenting an innovative experimental participatory process through a recent case study, and the lesson learned from its application. The inter-municipal case study was implemented in Val Polcevera, Genova which includes five municipalities. This case study is characterised by numerous physical and social interconnections: the territory has homogeneous risk where residents and 14 schools are located in an area prone to flash floods. Giambelli highlighted the need for a wide range of expertise to coordinate the planning process and the need for actors that can facilitate the interaction between stakeholders; in this case-study CIMA covered the technical expertise and a group of sociologists facilitated the participatory approach with stakeholders. Giambelli explained it is crucial to involve the administration and relevant political figures in the planning process as they can promote the necessary actions. Furthermore, it is important to involve the critical stakeholder; in the Val Polcevera case study these included the school and municipalities organisations. Giambelli explained the various stages of this experimental participatory process (summarised in figure 3). After the first stage of activation, which serves to define a common objective, and inform everyone involved of future steps, a training was organised to increase knowledge and capacity, create a common language for the group, and create a working group to draft the final plan. Following the training, a phase of co-design occurred; this was achieved by organising two workshops which involved all stakeholders and participants. The first workshop was a participatory risk mapping, which located different hot spots for floods, and involved the valuable local stakeholder knowledge. The second workshop co-designed the actions to be taken by each stakeholder in each risk management phase; this created shared responsibilities and a common risk vision of the territory. The last phase of the process is the collaboration phase which mostly included municipalities and school managers in this case study. This phase produced a clearer definition of flood risk which informed the municipal plan, and produced shared and accepted actions by the municipalities and the schools.

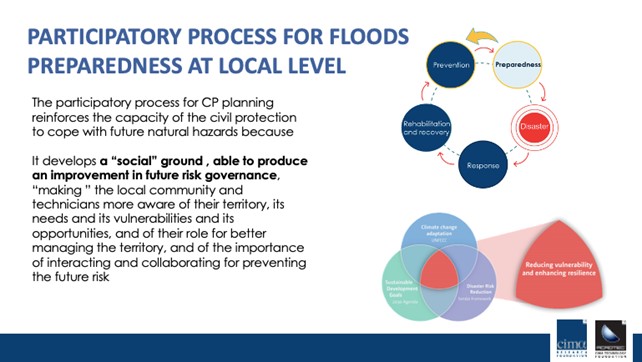

Figure 4: Marta Giambelli presentation slide summarising the stages, outputs, and positive impacts of the participatory process for flood preparedness at local level which she presented.

Giambelli summarised that this successful case-study fostered local vulnerability and capacity assessment, and informed intermunicipal urban planning. Furthermore, it fostered institutional capacity and empowered technicians with deeper technical knowledge. Most importantly, it fostered the community capacity. In summary, the participatory process presented allows to render institutions more capable to manage emergency and to cope with events even if not foreseen, as well as implement prevention measures. This process develops a social ground which can improve future risk governance, as explained in Giambelli’s closing presentation slide (figure 4).

This webinar highlighted the parallels between wildfire and flood risk management in the Mediterranean; both natural hazards are being aggravated by land use changes and climate change. Plana, Ortuño, and Giambelli all highlighted the importance of effectively involving various local actors in risk management actions by providing specific examples of their experience in successful risk management projects. These examples and reflections presented effective methodologies, identified crucial stakeholders to involve, and highlighted meaningful considerations for the knowledge gaps in European participatory risk management.

Check here the Questions and Answers that were not answered during the webinar session.

*CTFC and CIMA are currently involved in RECIPE project (https://recipe.ctfc.cat) from the European Mechanism of Civil Protection, undertaking integrated and participatory risk management approaches. The municipality of El Bruc is where the pilot site of the project in Catalonia is implemented.

Leave a Reply