Written by Lucía de la Riva

Ecosystems have relied on fire for millions of years to survive, and the development of human civilization has been possible thanks to fire. However, over centuries the relationship between modern societies and fire has been deteriorating, and the occurrence of extreme wildfires in the last few decades has increased the fear of this natural element. Researchers and experts agree that what might seem a threat to nature and humans, is in fact a resource to reduce the risk of having large wildfires if used wisely. Integrated Fire Management (IFM) aims at this by using expertise from a wide and diverse community that includes scientists, citizens, land managers and firefighting services.

Humans and many living things depend on fire to increase their chances of survival

Fire might seem dangerous for ecosystems, but for millions of years, it has been one of the many factors making some ecosystems around the world be the way that typically characterizes them. As fire existed in some ecosystems, originally caused by lightning, many living things ended up adapting to it by developing traits that increased their chances of survival in the event of a fire.

An example is the Mediterranean ecosystem, which is full of “pyrophyte” species (from Greek, pyro: fire and phyte: plant). One such species is the Aleppo pine, whose seeds are enclosed in pine cones that open thanks to the heat from a fire. This releases the seeds that can then reach the ground and germinate.

Figure 1: Pine cones in P. halepensis before (left) and after (right) a fire. Source: J. G. Pausas

Organisms in “fire-prone ecosystems” (where fires are likely) that are adapted to fire are more precisely adapted to what is called a “fire regime”: the set of characteristics of the fires occurring in a particular place over the years. These are when and where they happen, how big they are, how much heat they produce, and how fast they grow. How living things there get nutrients, reproduce and interact between themselves and with their environment depends on fire to different extents.

Healthy ecosystems are a complex network of interacting elements that have reached an equilibrium where “everything is in its right place”, including the fire regime. If one piece changed, the entire system could collapse. In other words, a change in the fire regime of fire-prone ecosystems, with characteristic plants, animals and other living things used to live with fire, could have devastating results, including biodiversity loss.

Human evolution took a giant leap when our ancestors learned to master fire. This opened a world of possibilities: cooking, heating, protection from predators, etc. Modern society furthered its use to develop industry and, hand by hand, the economy. It is an element of cultural festivals in Europe too such as Bonfire Night in the UK and Las Fallas in Spain.

Fire has also been an agricultural tool. Farmers in the Pyrenees have been cutting and then mildly burning forests for agriculture for thousands of years. This traditional use of fire to manage the land, together with natural fires caused by lightning, has been shaping European landscapes. We can find several examples, one of them in the coastal heathlands of Northwestern Europe, whose biodiversity and dynamics are the way they are now thanks to grazing and controlled fire.

A result of the combination of pastoral and natural fires is “mosaic landscapes” where vegetation spreads unevenly. The existence of patches of vegetation has an advantage: in the event of a fire, it lowers the chances that it turns into a large wildfire. This is because vegetation fuels fire, and, when vegetation is evenly spread and forests are packed with it, fire finds fuel to burn. In this scenario, there are also fewer spaces for the firefighters to safely suppress the fire.

Human action, directly and indirectly, has caused changes in the landscape that have increased the risk and damages of wildfires

Phenomena such as the abandonment of rural areas, industrialization, and preference for fossil fuels over wood helped vegetation overgrow.

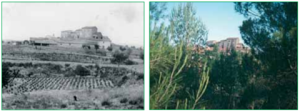

Figure 2: Landscape around a country house in Castellolí, Catalonia, in 1908 (left) and 2001 (right), with an overgrowth of fuel due to a change in agricultural activities. Source: Costa et al. (2011)

In parallel, society started to see fire as a threat that must be eliminated. As a response, efforts were put into suppressing fires. It sounds like irony, but fire suppression makes fires worse. This is called the “firefighting trap”: if we suppress all fires, there´s no barrier to vegetation growth and the amount of fuel for fires builds up.

All this together with climate change is changing the fire regimes. One of the negative impacts of this is that the traits of fire-adapted organisms that have worked till now might not work anymore. Furthermore, it is becoming more and more difficult to try to predict wildfire episodes, which would help to prepare for them. Finally, there are some fires so dangerous that firefighting services can´t control them (“extreme wildfires”), leading to huge losses. A lack of enough climate-change-adaptation strategies in place increases the problem in Northern Europe.

In fact, between 2000 and 2017, forest fires in Europe burned 8,5 million ha and killed 611 people, including firefighters and civilians. Economic losses were over EUR 54 billion. This is nearly EUR 3 billion/year, and it is expected that go up to over EUR 5 billion/year in Greece, Spain, France, Italy, and Portugal by 2070 – 2100 (Forest Fires report).

We can fight fire with fire

Considering that fire has an ecological role and that there´s a need to reduce the risk of wildfire due to the accumulation of “fuel load” (amount of vegetation), IFM uses fire as a tool to reduce the risk of large fires by the so-called “prescribed burning”. This is a fire intentionally set under controlled conditions by specialists and that has a particular goal: reduce the fuel load, preserve habitats, etc.

Prescribed burning was introduced in Europe to substitute the agricultural use of fire or management systems that fell into disuse. Nowadays in Southern Europe, it is a common practice in Portugal, Spain, France, and Italy. France started its prescribed burning programs in the early 1980s. In Catalonia, in Northeastern Spain, a group of specialized wildland firefighters called GRAF (Group of Support to Forest Actions) began to use fire as a management tool around twenty years ago.

Particular examples of how prescribed burning has been integrated into landscape management strategies are the initiatives “LIFE Granatha” and “Landa Carsica” in Italy, and “LIFE Montserrat” in Spain, where it is helping to improve biodiversity and habitat besides decreasing wildfire risk.

Figure 3: Trained specialists carrying out prescribed burning. Source: Pau Costa Foundation.

Integrated Fire Management involves a different way of thinking and doing by many actors that seeks being able to live with fire

Globally, scientists and experts agree that there is the knowledge, science, and tools to reduce the risk of extreme wildfires and reduce their impacts: through IFM. Adopting the IFM approach involves a paradigm shift: from investing in fire suppression to the development of more resilient (fire-tolerant) landscapes and communities better prepared to live with fire.

IFM grounds on several elements: scientific, practitioner and local knowledge; social diversity (e.g. nationality, gender, age, culture); exchange of knowledge between professionals from different countries, fields, and sectors (public and private, and industry and research organizations); and bringing in experiences, knowledges and lessons from what has worked well in the management of other risks like floods.

PyroLife prepares a new generation of researchers in Integrated Fire Management

PyroLife trains the next generation of researchers and professionals in IFM through the development of a common perspective that, besides their particular field of research, considers multiple disciplines such as fire ecology and behaviour, economics, governance, and communication. Furthermore, it facilitates knowledge transfer between Southern and Northwestern Europe. It is the first large and integrated doctoral training program on wildfires globally, being a leading example for training our future leaders.

At times of climate change, increase of the risk of wildfire and social neglect of the ecological role of fire, learning to live with fire is key to maintain healthy ecosystems, reduce the negative impacts of wildfires, and therefore improve our wellbeing. PyroLife provides the training the next experts need to be able to develop resilient landscapes and communities with the approach of Integrated Fire Management.

References

Fire and ecosystems

Lundquist, J.E., Camp, A.E., Tyrrell, M.L., Seybol,d S.J., Cannon, P. and Lodge, D.J. (2011). Earth, wind, and fire: abiotic factors and the impacts of global environmental change on forest health. In: Forest Health. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://www.fs.usda.gov/research/treesearch/39129

Mosaic landscapes

Costa, P., Castellno, M., Larrañaga, A., Miralles, M. & Kraus, D. (2011). La prevención de los grandes incendios forestales adaptada al incendio tipo. Unitat Tècnica del GRAF, Cerdanyola del Vallès, Barcelona, Spain.

Rigolot, E. & Lambert, E. (2021). Case Study 13.2 Prescribed Burning: An Integrated Management Tool Meeting Many Needs in the Pyrénées-Orientales Region in France. In Rego, F.C., Morgan, P., Fernandes, P., Hoffman, C. (2021). Integrated Fire Management. In: Fire Science. Springer Textbooks in Earth Sciences, Geography and Environment. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69815-7_13

Vandvik, V. (2021, May 26). Understanding the ecological and evolutionary imprints of humans on biodiversity climante on coastal heathland. Available at https://pyrolife.lessonsonfire.eu/a-burning-issue-understanding-the-ecological-and-evolutionary-imprints-of-humans-on-biodiversity-climate-on-coastal-heathlandv2/.

Changes in fire regimes

Castellnou, M., Bachfischer, M., Miralles, M., Ruiz, B., Stoof, C. R., & Vilà‐Guerau de Arellano, J. (2022). Pyroconvection classification based on atmospheric vertical profiling correlation with extreme fire spread observations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 127(22). https://doi.org/10.1029/2022jd036920

Losses due to wildfires

European Commission. (2018). Forest Fires, sparking firesmart policies in the EU (rep.). Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_6465.

Prescribed burning

Ascoli, D., Oggioni, S. D., Barbati, A., Tomao, A., Colonico, M., Corona, P., Giannino, F., Moreno, M., Xanthopoulos, G., Kaoukis, K., Athanasiou, M., Colaço, C., Rego, F., Sequeira, A. C., Acácio, V., Serra, M., Plana, E. (2022, March 31). Smart-Solutions for Wildfire Risk Prevention: Bottom-Up Initiatives Meet Top-Down Policies Under EU Green Deal. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4071721 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4071721

Paulo M Fernandes, Eric Rigolot. 13. Prescribed burning in the European Mediterranean Basin. Global Application of PRescribed Fire, 2022. ⟨hal-03549228⟩. Available at: https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03549228/document

Integrated Fire Management

Stoof, C. R., & Kettridge, N. (2022). Living with fire and the need for Diversity. Earth’s Future, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.1029/2021ef002528

Castro Rego, F., Morgan, P., Fernandes, P., Hoffman, C. (2021). Integrated Fire Management. In: Fire Science. Springer Textbooks in Earth Sciences, Geography and Environment. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69815-7_13

Leave a Reply