PyroLife International Symposium: Towards an Integrated Fire Management

Highlights from the fourth PyroLife Symposium webinar on June 24, 2020 by Kathleen Uyttewaal.

On June 24, Bertram de Rooij told us a story. As a landscape architect, applied senior researcher at WUR, and volunteer firefighter, it was far from the usual campfire story.

And yet, some common threads of stories since time immemorial like creativity, imagining the future, and learning valuable lessons with people along the way all wove their way into Bertram’s narrative.

He urged us to think about Envisioning Futures and Enabling Landscapes. Landscapes, after all, set the scene where everything comes together: ecological, social, political and economic processes. Under the paradigm of climate change, we tend to think about risk and everything we might lose in our landscapes, yet Bertram sees opportunities—especially if we consider nature-based solutions to climate change. These approaches require us to look “both forward and backward” and place importance on integrated landscape planning, as well as the kinds of narrative and ownership promoted in these spaces… who’s going to build these landscapes? And for whom? How do we know we’re tackling the right solution—are we looking at the problem deeply enough? Nature-based solutions intend to include and connect to other functions, like creating agricultural and recreational space, which maintain the natural qualities of the landscape over time. They are cost effective, provide environmental, social and economic benefits, and help build resilience. To implicate nature-based solutions, one must really understand both the physical and social landscape where we’re working. That is, nature-based solutions will be complex, involve many scales of action and all kinds of diverse actors, with an important focus on social justice.

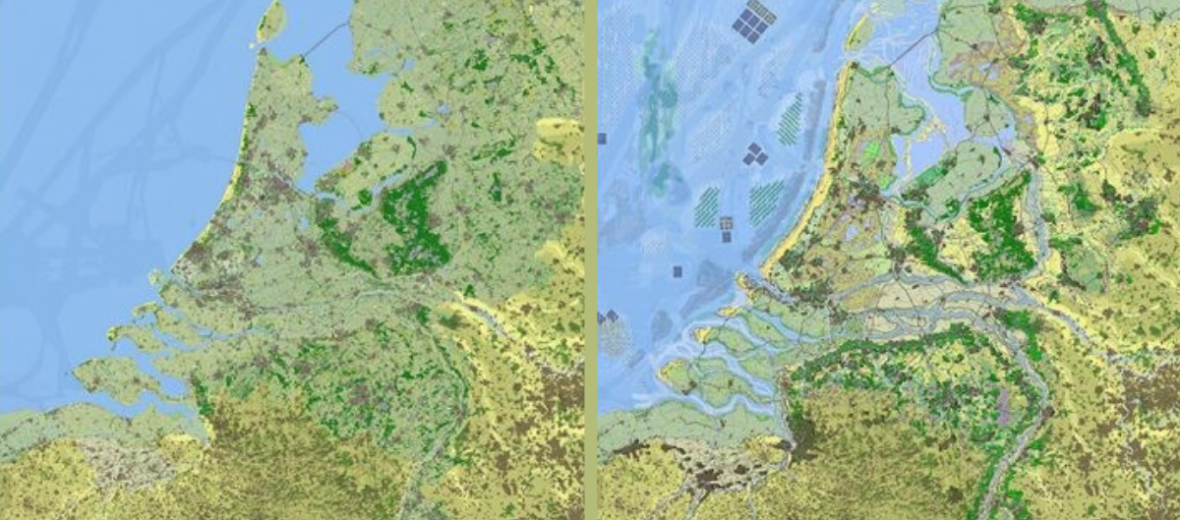

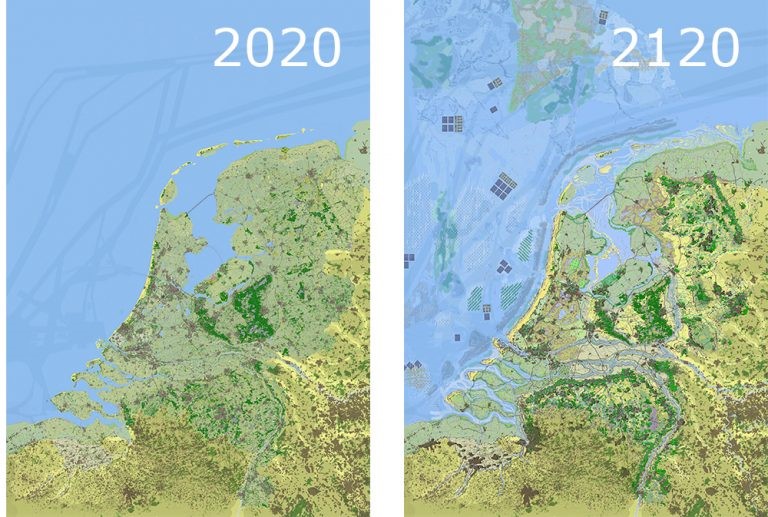

To ground this philosophy, Bertram quipped: “God created the world, but the Dutch created the Netherlands.” Lots of historical struggle occurred with controlling the waters for centuries. But slowly it transformed into an opportune, engineerable landscape. Constructing the Dutch landscape has been a constant process of innovating and improving, with a focus on technical hard defense of keeping sea water out. But these days, multiple other risks compound with rising rivers, sea levels, and even unprecedented drought in the land of water. It is time to move from a reactive mindset of crisis and disaster management to adaptive spatial planning and prevention, in the land of water and beyond.

So how do we implement these approaches? That’s quite complex and context specific. No standard solution exists—though that is part of the power of these approaches as well. Bertram considers all these adaptation opportunities best in a development context. By focusing on the positive impacts of adaptation (with climate change as a main driver), we are capable of creative, appealing and equitable changes. Action is needed at every level in society. For this, real participatory processes are essential in order to build shared interest and common ground. As a planner behind the scenes, it is important to adopt a holistic and integral view: multilevel, multi-actor, multi-scale, with the ability to “zoom in and zoom out” of challenges, value strategy and process equally, and connect to different actors in the field. This planning requires, essentially, bringing the future into the present.

Bertram worked to integrate much of this vision into the Netherlands 2120 project: a landscape design strategy that envisions how the ideal Dutch landscape will look in 100 years. It intends to “combine everything with everything:” sea and land areas, climate adaptation, circular economies, and creating a more inclusive society. Similarly, he created linkages in the PLACARD Project, bringing the climate adaptation community and disaster risk community together for fruitful discussions and planning. For that, it was key to find the correct narratives. He asks, “How can you get together to cook an appealing story? For whom? And what should be that strategic narrative? For what purpose?” In classic storytelling fashion, he gave us an answer in a simple yet profound moral: something that is easy to say, yet often so difficult to do: it starts with common understanding. It’s understanding the linkages of the personal worlds of inhabitants, their landscape values, to their systems of electricity, water availability, and connections to other risks (like drought, fire, earthquakes, etcetera).

Looking closely at his own work, Bertram admits that a new character is emerging in the story of the Netherlands: wildfires. For these new landscape and risk scenarios, he says, we need to create new values and opportunities. The good news is that many tools already exist to incorporate this character: envisioning the future, focusing on what will be required for success, defining high impact initiatives, mobilizing resources to take action, reflecting on and refining strategies. We must remember to zoom out and in on the national, regional, and local levels. The narrative of “Living with Fire” must be flexible, and appeal to all different stakeholders. By creating the right kind of story, we can start with a shared and connected vision on many levels. And finding this common ground will foster positive and creative agents of change for years to come.

Leave a Reply