A blog post by Carmen Rodríguez

The wildfire problem: do we really know what it is?

It is not very difficult to justify the importance of wildfire research. It is rather easy to resort to some statistics about the large burned areas or devastating effects of fire in different countries around the world, such as Chile, Canada, the US, Portugal or Greece. Also, often the images speak for themselves. And when not, maps of burned areas or testimonies of survivors do the rest.

Our recently published research, however, takes a slightly different starting point. It reflects upon the very nature of the wildfire problem itself. And how come that in fire-prone countries, like Mediterranean Europe, where there is a lot of history of dealing with wildfires, the problem remains far from being solved. Why? What are we doing wrong? Is it possible that we are looking at this from the wrong angle? This is the starting point of this paper. The idea that maybe, if we looked at wildfires from a different perspective, we may realise that there are a number of factors that we are paying limited attention to, but that actually are very relevant to the configuration of current wildfire regimes, and consequently of the resilience of the territories we inhabit.

The way we frame a problem determines how we search for solutions

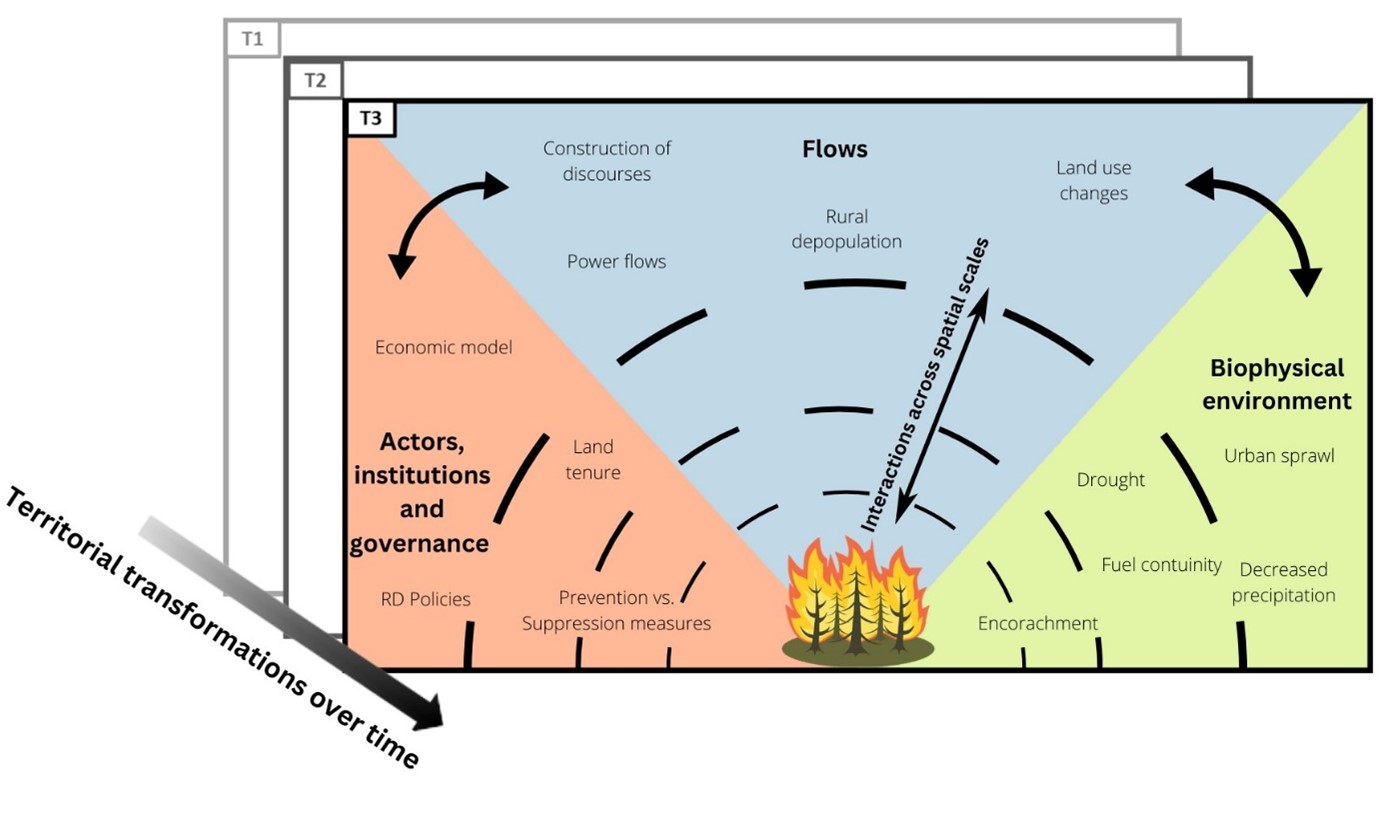

Problem framing relates to the way we (society) look at and deal with a specific issue. In fact, the very definition of whether something is a problem or not, is also a social construct. But we are not questioning that here. We take as a starting point that wildfires are indeed a problem in Mediterranean Europe. But we question whether our framing of wildfires is the best one to actually solve it. For example, when we frame wildfires are as an ecological disturbance, understanding the role and evolution of fire in the ecosystems is key, and policy and management goals are oriented towards restoring some sort of natural balance. Alternatively, if wildfires are framed as civil protection issue, understanding fire behaviour takes precedence, as it is essential for enhancing preparedness, and facilitating suppression actions during the emergency itself. In reality, both these framings coexist, yet the civil protection approach dominates over the ecological one. In our research, we suggest an alternative framing, and explore what the implications of that are. What if we understood wildfires as a territorial problem? We know that, at least in fire-prone areas such as Mediterranean Europe, ecosystems and communities have co-evolved with fire over millennia. Building upon that fact, we conceptualised fire-prone territories as the outcome of multiple and highly complex interactions (social, political, economic, cultural and ecological), which have co-evolved with specific wildfire regimes over time and space (See the figure below).

Graphic representation of a fire-prone territory. Source: Rodríguez Fernández-Blanco et al., 2024

By looking at wildfires and fire-prone territories, we showcase the importance of power struggles, diverging worldviews or spatial inequalities in shaping the very same disturbance regimes that are ultimately impacting the well-being of the communities that live in these areas.

Implications for the resilience building process

The paper also seeks to test the relevance of this approach in an empirical setting, and makes the case about what does all of this imply for building resilience. In order to do that, however, the article zooms into the region of Valencia (Spain). Valencia may be considered a paradigmatic example of a Mediterranean territory in southern Europe. With intense tourist pressure on its coastal areas, contrasting with the land abandonment in rural ones, and exposed to high wildfire risk.

Example of abandoned land in La Serranía county (Valencia, Spain).

The paper finds how there is a significant distinction between the collective imaginaries across the urban-rural gradient. In rural settings, interviewees discussed wildfires as part of the larger issue of rural decline, and in some instances, there were clear assertions on how wildfires were a result of the institutional neglect they suffered. If we build upon the understanding that the ultimate goal of resilience building is the well-being of society as a whole, the relevance of bridging the urban-rural gap for achieving a more sustainable coexistence with wildfire appears as quite relevant.

Another point that the paper highlights is the relevance of addressing a highly complex issue like wildfires from a collective perspective. Taking the policy sector as an example, it is particularly difficult to do so when the public administration is so highly compartmentalised and specialised (which in resilience jargon is referred to as a “rigidity trap”). A consequence of this is that the opportunities and spaces for innovation are drastically reduced, therefore reducing resilience levels. In this regard, the lack of collaborative cultures also hinders trust building, which is a key element for facilitating collaboration across scalar scales.

Leave a Reply