Research article summary

Blog article by Judith Kirschner.

Original publication: Kirschner, J.A., Clark, J.R.A., Boustras, G., 2023. Governing wildfires – towards a systematic analytical framework. Ecology and Society, 28(2): 6. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-13920-280206

Highlights

- Local communities, states, and wider society have different interests, responsibilities, and capacities to deal with the root causes and impacts of escalating wildfire activity.

- A governance approach enables exploration of the decision-making and decision-taking processes and structures through which wildfire risk management is made.

- Our framework enables enhanced understanding and comparison of wildfire governance settings by zooming in on actor participation and collaboration across organizational levels, territorial scales, and networks; examining local place-based context and values; and consideration of different modes for wildfire risk adaptation and anticipation.

From fighting the flames towards governing the system: why is this work important?

Wildfires have made many headlines over the past years: they burned in the Amazon, in the Arctic, during last summer’s heatwave in greater London, and around the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine. Scientists know much about why these fires occur and the impact they can have. Very often, wildfire ignition is as much a product of human activity as of natural events, and increasingly their expansion is amplified by profoundly transforming climate, landscapes, and lifestyles.

In Global North countries, the default option to contain wildfire risk is to expand emergency response capacities, for example by using airplanes or investing in technology for early detection. And while not all ignitions can always be prevented and suppressed, experts have many ideas for reducing the disaster potential of a wildfire before it is burning. For example, new building materials can reduce the risk of buildings catching fire, while targeted incentives in rural areas to change how land is managed can curtail the spread of high-intensity fires.

But these ideas have been around for decades and are far from new – and recent damages and losses are outpacing ever-growing investments in firefighting. So do we need new approaches to meet the global wildfire challenge?

In our article, we step back from the tangled web of tactical decisions aimed at directly fighting the flames, to look at the broader socio-cultural context of wildfires with its rich and geographically varied institutional processes, structures, and systems. In doing so, we pay close attention to the hitherto largely neglected aspects of fire in the landscape – a powerful invention in human history, but also a naturally occurring process that humans have lived with for millennia offering diverse possible benefits for society and the environment as much as the risk of potentially devastating events.

How to describe and measure wildfire governance?

Wildfire governance [1] is a concept used to describe the sometimes conflicting, sometimes complementary interests, roles and decision-making responsibilities of actors and agencies in the wildfire sector. This includes authorities and non-governmental groups active in territorial planning, civil protection disaster risk management, or supporting cultural fire use. Notably, wildfire activity and the strategies to manage associated risks and benefits can be complex and greatly vary across local to territorial contexts.

Over recent years, scientists and practitioners have started paying attention to characterise the different governance settings supporting wildfire decision-making and decision-taking. To our knowledge, however, no comprehensive review has been undertaken of wildfire governance scholarship. Therefore, the goal of our research article was threefold: to provide an overview of emerging wildfire governance concepts, a summary of the challenges that exist, and a road map towards new anticipatory and adaptive approaches to living with fire.

To this end, we used the keywords ‘wildfire AND governance’ to find literature on the Scopus database and included additional cross-references. We also examined the Thomson Reuters Westlaw database to account for relevant legal literature. Finally, we turned to the latest developments in the wider natural resource governance literature, proposing an analytical framing of wildfire governance with four pillars. In the following we summarise some highlights of our findings.

[1] Governance: “the processes through which public and private actors articulate their interests; frame and prioritise issues; and make, implement, monitor and enforce decisions” (FAO, n.d.).

State of art – wildfire governance literature and theory

We examined 98 studies on wildfire governance, published from 2005-2022. Here are some key insights of our review:

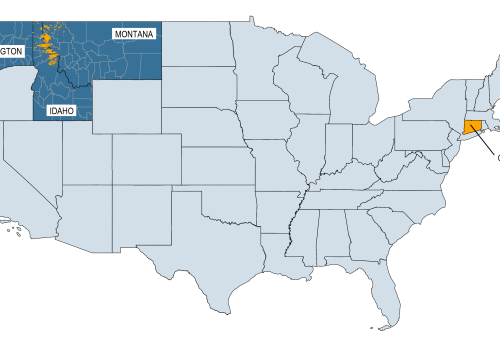

- Geographically, most studies on wildfire governance are covering global north contexts like the US (42% of the literature sample) and Australia (13% of the sample), leaving gaps in knowledge in majority world countries.

- 58% of all studies generically examine wildfire ‘governance’ or ‘risk governance’, without discussing how the concept was defined or operationalised.

- The remaining studies treated diverse governance settings, characterised by ‘adaptive governance’ (in 13% of studies), ‘collaborative governance’ (9%), ‘network governance’ (8%), ‘multi-level’, ‘good governance’, ‘polycentricity’ and ‘anticipatory governance (3%, respectively), ‘participatory’ and ‘reflexive governance’ (2%, respectively).

A brief overview and description of selected governance theories are provided at the end of this article. The studies and frameworks we examined are beginning to generate valuable and context-specific insights on governing wildfires under consideration of different drivers, vulnerability, and impact. However, we noticed a lack of consistent definitions and precision in the corpus of literature. Studies often build upon specific wildfire events, rather than focusing on common processes and contexts across and between different wildfire events.

In the following, we outline our suggested framework to advance thinking of wildfire governance.

Governing wildfires: towards a systematic analytical framework

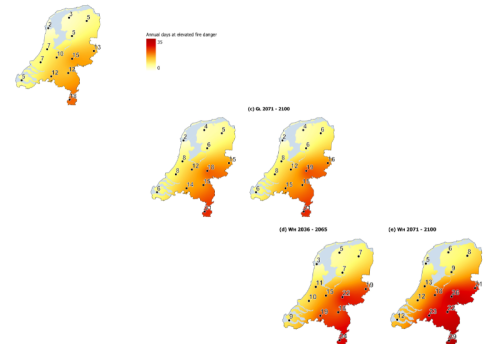

We engaged and complemented our literature analysis with work by Cumming et al. (2020), proposing a systematic analytical framework with four pillars as follows (fig. 1):

Process – the interactions between actors to achieve successful governing outcomes like cooperation, negotiation, or learning. For the governance of wildfires, empowering actor participation could increase the capacity to manage wildfire risk, but more research is needed to also tackle challenges of stakeholder involvement in different contexts.

Structure – various formal and informal institutions participate in wildfire governance procedures. We found collaboration and coproduction to be essential to bridge and connect stakeholder groups across organizational structures, territorial scales, and networks. Further research could give better insights on underlying motivations and incentives in collaborative settings.

Context – the set system context shapes everyday decision-making emerging from different types of knowledge, attitudes, and values. Wildfire governance is highly variable across diverse contexts, also because of the diverse formal and informal rules, values and knowledge types characterising local wildfire incidence and vulnerability.

Outcome – the practical action steps resulting from interactions between institutions, organisations, and people. Effective institutions to address the wildfire crisis will require adaptation to and anticipation of wildfires. Crucially, risk management strategies must be uncoupled from past observations, to increase flexibility and learning in future trajectories of change.

Fig. 1 (figure from: Kirschner et al. 2023).

Altogether, the framework could enhance wildfire governance theorising, and offer a background for developing and testing hypotheses by enabling the definition, measurement, and comparison of different wildfire governance systems. Crucially, it needs to be applied in collaboration with practitioners – to bridge the gap between academics and policy practitioners, enhance research utilization, and to keep wildfire governance research relevant to real-world issues.

Despite the investments made and knowledge gained over past decades and after devastating wildfire disasters in particular, wildfires are likely to pose significant management challenges also in the near and long-term future. Our governance framework could contribute to boost collective capacities – for headlines of the years to come to be re-written, by initiating a profound transformation in how we deal with the global wildfire challenge.

Brief overview of key governance concepts identified in the systematic review:

Generic governance (not further specified, or generally referred to as risk or ecosystem governance): General reference made to formal and informal institutional context and procedures for decision-making and decision-taking.

Adaptive governance: Adaptive governance describes the social and institutional settings that facilitate or impede adaptation, flexibility and learning processes (Folke et al. 2005, Armitage et al. 2012, Chaffin et al. 2014). Closely related to the concept of resilience, where systems are limited in responding to dynamic biophysical and social factors, thus building up capacity to adapt, reorganise, reshape, and transform to a new state after disturbance.

Collaborative governance: Emphasises joint action and self-organised sharing of resources and information to reach mutual objectives and benefits. Stakeholder groups can be formal or informal arrangements of government authorities, civil society groups, communities, and private sector actors (Gray 1985, Bodin 2017, Emerson et al. 2012).

Network governance: Patterns of coordination and communication amongst various autonomous actors and organisations, connected by networked exchanges and flows of resources, information and values. Networked governance can allow for more flexible and adaptive responses to complex problems (Provan and Kenis 2008, Ostrom 1990, Carlsson and Sandström 2008).

Multi-level governance: Emerged in the 1990s in studies on the interactions in the European Union. Describes the vertical integration of governance scales and organisational levels in dealing with complex and interconnected problems of modern society through negotiation, coordination, and cooperation amongst various stakeholder groups (Hooghe and Marks 1996; Berkes 2008; Jessop 2013).

Participatory governance: Joint decision making expected to increase legitimacy, accountability and governance effectiveness by empowering non-state actors through opportunities for participation and representation (Peña-López 2001). Outcomes of participatory governance depend upon context specific circumstances (Newig 2009).

Polycentric governance: Self-organised governance arrangement comprising multiple autonomous centres of decision-making, opposed to one single, state-centred authority or privatisation. Allows to account for knowledge and values in different contexts. Comprises networks, collaboration and partnerships aiming to solve shared conflicts through mutual relations (Ostrom et al. 1961; Ostrom 2010).

Anticipatory governance: Strategic forecasting and flexible scenario planning to anticipate and prepare for uncertain possible futures. Aims to proactively build up organizational and adaptive capacity to respond to the variance in future events beyond known records, also by engaging various stakeholder groups (Quay 2010).

References

Armitage, D., De Loë, R. and Plummer, R., 2012. Environmental governance and its implications for conservation practice. Conservation letters, 5(4), pp.245-255.

Berkes, F. 2008. Commons in a multi-level world. International journal of the commons, 2(1):1-6.

Bodin, Ö. 2017. Collaborative environmental governance: achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science, 357(6352):eaan1114.

Carlsson, L. and A. Sandström. 2008. Network governance of the commons. International Journal of the Commons, 2(1):33-54.

Chaffin, B. C., H. Gosnell, and B. A. Cosens. 2014. A decade of adaptive governance scholarship: synthesis and future directions. Ecology and society, 19(3).

Emerson, K., T. Nabatchi, and S. Balogh. 2012. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of public administration research and theory, 22(1):1-29.

FAO. N.d. Policy Support and Governance Gateway. Accessed on 23rd of June, 2022, https://www.fao.org/policy-support/governance/en/

Folke, C., T. Hahn: Olsson, and J. Norberg. 2005. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour., 30:441-473.

Gray, B. 1985. Conditions facilitating interorganizational collaboration. Human relations, 38(10):911-936.

Jessop, B. 2013. Hollowing out the ‘nation-state’and multi-level governance. In A Handbook of Comparative Social Policy, Second Edition. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Marks, G., Hooghe, L. and Blank, K., 1996. European integration from the 1980s: State‐centric v. multi‐level governance. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 34(3), pp.341-378.

Newig, J., 2012. More effective natural resource management through participatory governance? Taking stock of the conceptual and empirical literature–and moving forward. In Environmental governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge university press.

Ostrom, E. 2010. Beyond markets and states: polycentric governance of complex economic systems. American economic review, 100(3):641-72.

Ostrom, V., C. M. Tiebout, and R. Warren. 1961. The organization of government in metropolitan areas: a theoretical inquiry. American political science review, 55(4):831-842.

Peña-López, I. 2001. European governance. A white paper.

Provan, K. G. and P. Kenis. 2008. Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of public administration research and theory, 18(2):229-252.

Quay, R. 2010. Anticipatory governance: A tool for climate change adaptation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(4):496-511.

Leave a Reply