Interview with Lara Steil and Peter Moore

Written by Lucía de la Riva

For this blog post, I interviewed Lara Steil, Forestry Officer (Fire Management) at FAO since July 2022, and her predecessor Peter Moore, now Director of Natural Resources Fire & Carbon Pty Ltd. For 17 years, Lara was the coordinator of the interagency department at the National Center for Wildfire Prevention and Suppression in Brazil (IBAMA, Prevfogo), focusing on national and international cooperation and the involvement of indigenous and rural communities in IFM activities. Peter has worked on natural resources and fire management for over 40 years all over the world: Africa, Australia, East Asia, Europe and North and South America. His vast expertise includes management, policy, operations, and training.

We deepen the concept of Integrated Fire Management (IFM) through two voices who have a sound knowledge of fire management thanks to their long and international experience.

Left: Lara Steil. Right: Peter Moore.

In a previous post, we introduced the concept of IFM. How would you define it?

Peter: 90% of fires are caused by people. That means that fires are a reflection of society, communities, individuals, engagement sectors, etc. IFM it’s all about people and getting to know them, how they talk to each other, how they interact, how communities are arranged. The integration is about bringing together all those views and perspectives, all those aspects of how humans use, relate, and interact with fire in a sensible way. This is complicated but, at the same time, it´s what makes IFM so wonderful.

Lara: I would add that IFM is not really a new approach. Maybe what it´s new is the change from the suppression of fires from the ecosystems to a holistic approach where the benefits of fire are considered and the communities play an important and central role.

Peter: That´s actually very important: the term IFM was first used in the early 80s. At that time, it meant integrating together all the different things you needed to do (meteorological information, fuels information, suppression capacity, etc.) to get organised to suppress fires. Since then until now, 40 years later, we’ve understood that it’s actually about integrating other things, like communities, where groups of humans get together in a sort of collective way where they understand each other and share common interests.

IFM seeks to increase the benefits of fire and decrease its risks. Benefits of fire?! What are they?

Lara: There are many of them. Probably the most famous is the control of dry biomass in order to avoid large fires. Also, fire represents an element that shapes ecosystems and plays ecological roles inside them. For example, it breaks the dormancy of some types of seeds. Something very interesting is that many indigenous communities have known empirically about these benefits of fires for ages, and they use fire in their territories to maintain the ecosystem healthy. For example, to encourage new growth of grass that provides food for many animals.

Peter: It’s worth thinking about why we think fire is negative. That´s because fire along with water and darkness are still innately three of the things that humans are most fearful of. As well as that primal fear, most of the time we come across fire, it’s as things like burning your fingers on the stove. We don’t see the positive combustion: inside motor cars, inside engines, heating houses… everything we use fire for every day in different ways that help us to live better lives and be more comfortable.

Why is IFM a good approach to the current wildfire challenges?

Peter: I think this harks back to what is IFM. The main source of ignitions is humans: by accident, misdirection, misadventure, etc., but it’s a key tool that humans need to use. Most of the world’s population, particularly in developing countries, is involved in agriculture, and they need fire as a tool for various reasons. So, given that it’s all people in their ecosystem, in their landscape, in their communities, then IFM is the way of giving all of the elements involved an opportunity to be seen, recognised, understood, and then brought together.

Lara: Yeah, and it’s very clear that the suppression approach is not working and we need to refocus our action on prevention.

Image of the 2017 wildfire in Pedrógão Grande, Portugal. Source: Reuters.

What is FAO´s approach to supporting IFM across the globe?

Lara: Our objective is to promote a paradigm shift from the zero-fire idea focused on suppression to holistic IFM. We focus on five elements we call the five Rs: (1) review and analysis: an understanding of what is really happening on the ground related to fire; (2) risk reduction: all the activities related to prevention of fire ignitions, fire travel across the land and fire impacts; (3) readiness: the need to be prepared to fight fires that will occur that we do not want; (4) response: the suppression of the fires that we don’t want in the ecosystems, in nature; and (5) recovery: guaranteeing the community welfare after a fire, repairing infrastructure and restoring the landscape (see the FAO strategy on forest fire management here).

Lara, you have worked coordinating the interagency department at the National Center for Prevention and Fighting Fires in Brazil. IFM involves collaborative work between multiple and varied profiles. What are the key elements for making this fruitful?

Lara: This is a huge challenge. For me, if we want to really have good results and outcomes, the main word here is dialogue. We need to dialogue, dialogue and dialogue with all the stakeholders involved in fire management with transparency and openness. An amazing facilitator or moderator is also key.

What policy is needed to support further implementation of IFM approaches? And what kind of policy-makers need to create those policies?

Peter: One of the things that’s really important is the review and analysis to understand influences and factors of fires occurring: why they’re happening, why they’re negative, what their positive implications are, and whom they are affecting. Once that’s understood, it’s a case of asking: how do we get the policy attention? Who needs to have attention on this? Which policies? One of the issues is that, traditionally, Forestry was the landscape fire management agency, and I’ve been doing it for a very long time, but there are other policy sectors (finance, planning, development, land development, agriculture, etc.) that also need to be part of the discussion. These days, even more importantly, there are things like environment, climate change, ecosystems restoration, and sustainability, but also health; there’s an emerging recognition of the impacts of fires on health.

If we need to engage those policymakers, the review and analysis side of things needs to understand those sectors and why they should be interested. For example, treasury should be interested because if you reduce the risk, you are more ready, respond more effectively and restore more effectively, build back better. Then, the cost to the country is reduced, and not just in lives, but also in rebuilding and restoring.

We can look at the lead that Portugal has taken and the way they’ve responded to the very severe fires they had. Portugal’s recent history of fires runs back to 2003 when they had some very, very severe events. They had three or four more examples of bad fire seasons. I think it was in 2017 when just over 100 people died in two major fires. And the Portuguese said: “hang on, this isn’t working. Who else needs to be involved? How do they need to be involved and how do we change this?”. So, they had lots and lots of dialogue, conversations, rhetoric, discussion, engagement, active listening; just letting people talk, express themselves, and then working out how to integrate those views and what was needed, which was not suppression capability. One problem identified in Portugal is that there is too much biomass in the landscape. “OK, how do we change that, and how do we do that in a way that’s sustainable and acceptable to the communities?”, and that’s the direction Portugal is going now.

The challenge here is that there are policy-makers who are willing to dialogue and others who are not. How do we change that?

Peter: As Lara said, one of the things is brilliant facilitators, having the right people.

Many years ago, there was a gentleman named Harry Luke who was the first Forestry Officer in fire management in Australia; he was appointed in 1938. He said there are two graphs: one is area burned and the other is government funding, and the two are offset. The area burned goes up and then your funding goes up. Then, as your area burned drops off, because you have one, two or three quiet seasons, the funding drops off. So, the mayor of New Orleans after Katrina said a couple of years later, when I talked to him: “Never ever let a good disaster go to waste”. He means that you have to have the review and the understanding and you have to know who needs to be talked to. Then, when the politicians are alert and the focus, the media and the opportunity exists to say something sensible and systematic and clear that’s supportable, we need to be able to do that quickly and take that opportunity. Fire management has to move in that direction.

In communication as well…

Peter: Yeah, completely…. listening. One of the advantages of working with FAO or your work internationally is that you get exposed to different perspectives and you start to understand. Or you don’t understand, but you get examples of different ways things are different. Things are different in Portugal compared to Sudan. Things in Sudan are different compared to Myanmar. Things in Myanmar are different compared to Brazil. Brazil is different to Australia. There are sorts of things that are in common or can provide a base for starting a discussion, but they are different places.

Peter, what are the main challenges Europe faces in terms of wildfires and the application of IFM?

Peter: Fires are about combustion, and combustion is about fuel, and Europe, in the last 20 to 30 to 40 years, has gradually adopted some policies that are enabling increased amounts of fuel and lowered amounts of management. So, it’s to do with funding, with prioritisation of governments, with importation of products rather than creation of products. Fuel buildup is an issue in certain places like Portugal, where they have realized that, but that problem also exists in many other countries. I personally think the places where it’s the most an issue are in Northern Europe: Germany and further up.

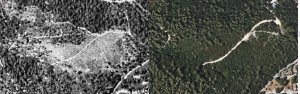

Comparison of the forest cover in Collserola, Catalonia, between 1445-1446 (left) and nowadays (right) . Source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya.

In Northern Europe, why?

Peter: Because they have forests that are in bigger trouble in being stressed by changing weather and climate and impacted by pests and diseases and they have less experience of fires. In the Mediterranean, people are more used to fires as part of their landscape and livelihoods, though there’s been changes in use in recent decades.

The other is the engagement, the governments. You have 27 countries in the European Union, so there’s 27 positions or perspectives or sets of ideas, probably more than that. Within each country, you have different levels of government; in Italy for example there are three. You have different agencies that might have an interest in fire or an accountability or responsibility for fire. Perhaps they talk to each other, perhaps they don’t; mostly they don’t, I would say. That’s the biggest challenge: how to create a process that can enable those people to talk to each other enough, to start to integrate their own perspectives into a better way of approaching the issues of fire management on the landscape.

It’s interesting that you mention Northern Europe, because there isn’t as much in the media about it as there is about Southern Europe.

Peter: That’s right, but there’s been a few examples in the last few years of, relatively speaking, very large fires or larger numbers of fires. I think that in Sweden or Norway, four or five years ago, they had more wildfires in forests in one day than they have had in the previous years put together.

Lara: Also in forests that take a long time to recover.

Peter: Yeah. And there’s a historical perspective to this too, because there have been very large damaging fires in Europe in the past. In Lower Saxony, in Germany, and in the middle seventies, 1975 I think it was, there was a very large wildfire. But, of course, 1975 is now nearly 50 years ago, so people have forgotten it happened. And that’s one of the other issues here: if people live, work and operate in an environment, if they have grown up in an environment where fires occur, they will likely have awareness and skills in fire management.

Firemen fighting the 1975 wildfire in Lüneburg Heath, Lower Saxony, Germany. Source: Hildegard Markmann.

In contrast, in most parts of Africa or most parts of inland Australia, where I grew up, fires were common at the end of every harvesting season; the wheat fields were all burnt, the barley fields all got burnt… It was a common thing, it stays as part of the discussion, as part of the communication, of the engagement in the community. But if you have a big fire every 20 years, then you have almost an entire generation of people that have no experience and no exposure, and it’s quite hard to maintain a dialogue around that, as Lara was suggesting, when it’s not very visible and high profile.

Peter, you have worked in Europe, Asia and Australia. Lara, you in Latin America; maybe even in more regions. What´s Europe doing well and what can we learn from other regions?

Lara: I think that Europe is well articulated and coordinated among the countries. This is very good because one country can support another one. This goes in the way that I was discussing: the dialogue.

I don’t have much experience in Europe yet, but I have the impression that the European approach is very much focused on suppression and, thinking of specific cases like Spain and Portugal, that the local knowledge on fire management is not considered as much as it could be. An empowerment and an asset provision of this local knowledge are necessary. The governmental agencies that work with fires need to look to it and go: “Oh, let’s see what these communities know about fire management”, and maybe we can learn from them. This is an experience that I and Brazil have: this work together with the local, traditional and indigenous communities. There´s a lot of knowledge there that you can empower and use in the agencies’ strategies and the national policies.

Training on fire management to the tsimane and movima indigenous communities in the Biosphere Reserve – BENI Biological Station, Bolivia. Source: UNESCO.

Peter: And they can be good illustrations of potential for Europe.

Europe does do some things very well: they’re very well funded; there are lots of money around. The research capacity is phenomenal, and not just in the physics of combustion, but in the social aspects of disasters more generally, in terms of restoration ecology and so on. There are lots of very, very good researchers, very good research institutions. Of course, it has the European Union, so there is a number of policies beyond national boundaries that enable things like resource sharing. This has been focused so far on suppression-related resources, but increasingly there are other types of exchange going on.

A good example of what I’m talking about is PyroLife itself. The European Commission has a funding for Innovative Training Networks (ITN), there’s a proposal for one, and out of that comes PyroLife, which is multidisciplinary, cross-agency. That’s a fantastic model and a good example. I cannot imagine an ITN equivalent being able to be created in North America or in Australia, certainly not in Africa or Asia.

Lara: Or Latin America?

Peter: Or Latin America. Europe has got some opportunities that are really worthwhile focusing on.

At the PyroLife conference, participants discussed on the needs of education on IFM. What´s your view?

Lara: This is very important because we are generating the future professionals in fire management. Nowadays we see that people working with fires learn about them on the way, while they are working; they don’t have previous theoretical-practical knowledge before starting their profession. In Brazil or Latin America, we talk a lot about environmental education. This is something to create awareness in the communities, which will see the environmental agencies setting fire in a protected area and need to understand that that fire is beneficial and not harmful. It is very important to create the holistic approach to fire management we´ve been talking about, especially in the case of community work,

Peter: The training and educating people through something like a PyroLife process is helping with that because you have more people in the community that can hold conversations, have discussions, explain things, and some of those people may end up feeding into curricula elements for teaching, for secondary science and primary school. And I think that’s all part of enabling or strengthening the potential for IFM and, of course, those things (school education, graduate, postgraduate and public) then feed into the policy pressure or the policy focus that you would like to generate around the issue.

When Catheljine (PyroLife Coordinator) and I first talked about PyroLife four years ago, maybe longer, in Coimbra, one of the things that I was really taken by was the fact that was multidisciplinary. These were young people who were going to come in and do research; some of them would move into a professional role, would continue research or might even end up somewhere completely different. But all would have had their structured exposure in a multidisciplinary and engaged discourse around this particular issue: fire management.

I was really enthusiastic about that because, when I look back over my shoulder, when I started in fire management in Australia there were 30, 40, 50 people across the country that were focused on IFM and on fire management – people across the country we had different terms for it. But now there are many many fewer. There are a bunch of people in research, but there’s almost nobody in management. I was really concerned, and still am really concerned, about the fact that we don’t have enthusiastic, well-informed, soundly-based managers coming into the area. We have some, but here in Australia it’s very, very thin and the same thing is potentially happening in other developed countries.

Lara: Just one more comment related to that. I think that through this educational process you can have a mentoring scheme in place. These people that have a lot of experience in fire management could share this knowledge with the new generation. The new fight of the new generation. It´s so important.

Peter: And that fades to something Lara started off: dialogue, dialogue, dialogue, dialogue, dialogue. You should never stop talking if you’re interested in fire management, you should never stop listening. PyroLife was a lot about that, and it’s really important for the education component, but it’s also important for the ESRs.

A round table at the PyroLife 2023 Conference. Source: Pau Costa Foundation.

What advice would you give to the ESRs who are finishing their PyroLife research projects?

What advice would you give to the ESRs who are finishing their PyroLife research projects?

Peter: My advice would be in two parts. One is: never stop listening and never stop talking to people about this. If you are going to the conference in Porto, listen to people, talk to people. If somebody gives a presentation and you think “I had no idea what that was about” or “I was inspired by it”, go and tap them on the shoulder. These people, no matter what their profile is, they’re all very happy to talk and the more you engage, the better.

The second thing, which is a bit more pragmatic, is that if you’ve identified something that you really are interested in, then pursue it and don’t necessarily let people pragmatise it, be practical and say “oh, you’ll never get a job doing that”, “you won’t be able to get any employment”, “you won’t be able to do this”, “you won’t be able to do the other”. I’ve managed to spend now 43 years in fire management full-time all over the world, and I was told very clearly that it was a silly idea to pick it up when I started.

There would be those two things. One is never stop learning, never stop asking, never stop listening, and then the second thing is to identify what you’re really interested in because you do need the interest. If you have the interest, you’ll find the energy, and if you find the energy, you’ll make some progress. And of course, there’ll be times, no matter what you’re doing, where you’ll be tired, have other demands on your time and families and all that sort of thing. We have two children… well, I call them “children”, but they are actually “very large things” these days. So, if you’re really enthusiastic have identified something, then that will help to keep it going.

Also, never stop reading, and not just on the combustion physics side of things. There’s a wide range of layers: as we mentioned, communities; how they interact, where they come from, what’s the definition of community, what types of communities are there, what are their governance structures, what’s their social development… There’s a whole body of work that you don’t need to understand all of it, but at least start to read some, to have an exposure.

Lara: Yes, I agree with Peter. Also, it doesn’t matter if one person is working with a very specific point related to IFM. It’s always important to keep working hard on that issue, but also to keep an eye on the big picture, on all aspects of fire, on all aspects of IFM. You don’t need to be an expert on every detail of fire management – this is probably impossible, but you can always, as Peter said, talk, discuss, listen abut other aspects of fire, integrated fire management from your colleagues, other experts or communities if you work directly with them.

As well it’s very important to know that every knowledge is important: ours, colleagues´, the community´s, high-level scientists´, etc. The knowledge of all the stakeholders is important.

My last word is: be brave to keep it going, but also enjoy what you are doing. This is very important: enjoy

Leave a Reply