Written by Sarah Meier. On the research article by Sarah Meier (University of Exeter), Eric Strobl (University of Bern), and Robert J.R. Elliott (University of Birmingham): The impact of wildfire smoke exposure on excess mortality and later-life socioeconomic outcomes: The Great Fire of 1910.

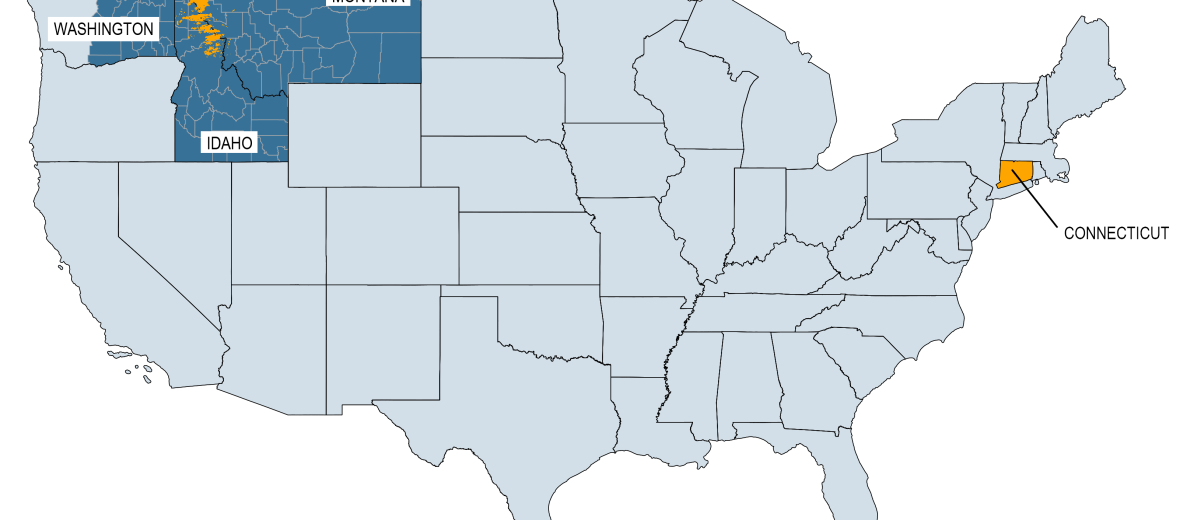

In the summer of 1910, a firestorm swept across the northern Rocky Mountains, consuming more than 1.2 million hectares in just two days. Known as The Big Burn or The Big Blowup, it became one of the largest wildfires in US history (shown in Figure 1). The Great Fire of 1910 burnt about the size of Connecticut or 1.5 times the size of Yellowstone National Park. While the immediate destruction of homes and forests was devastating, an often-overlooked consequence of the fire was the vast plume of smoke that travelled hundreds of miles, posing serious risks to public health far beyond the fire’s reach.

Although wildfires were not rare in this region, the scale of the disaster was unprecedented, leading to the establishment of strict fire suppression policies that remained in place for much of the 20th century. Yet, the Great Fire’s most enduring legacy may not lie in these policies, but in the significant health and socioeconomic effects it had on individuals exposed to the smoke, especially young children.

Figure 1: Burned area by the Great Fire of 1910 at the intersection of the states of Washington, Idaho, and Montana. The darker blue shaded colour denotes the study area.

The overlooked danger: smoke and health

While wildfires are often associated with their immediate destruction – devouring forests, homes, and infrastructure – the smoke they produce poses an equally serious threat. Wildfire smoke is composed of fine particulate matter and harmful chemicals, which can cause significant health problems, especially for vulnerable groups like children and the elderly.

At the time of the Great Fire of 1910, the focus was primarily on the economic damage. Specifically, residents were concerned about timber loss and the role of forests in preventing floods, and the health impacts of smoke exposure were largely underappreciated. In our study, we utilise historical data to investigate how the wildfire smoke from the Great Fire affected the health and later-life socioeconomic outcomes of young children who were exposed.

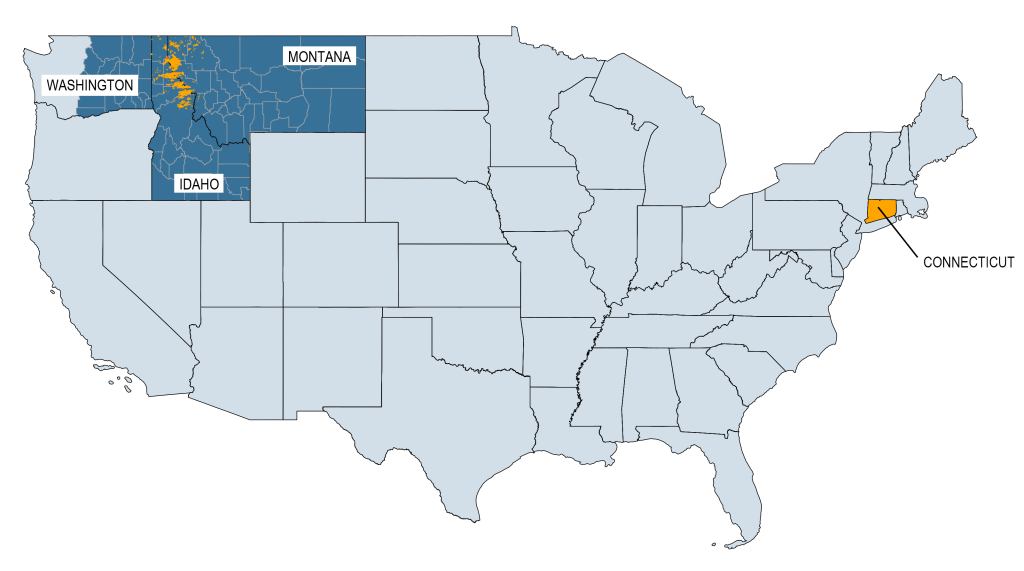

By combining historical fire perimeter maps with smoke emission and dispersion modelling, as well as digitised mortality records and census data from 1900 to 1940, we quantify both the short- and long-term effects of this event. Figure 2 shows the modelled smoke plumes implementing the smoke emission and dispersion modelling framework by BlueSky feeding historical information for each of the approximately 200 burn perimeters.

Figure 2: Modelled smoke plumes using the BlueSky framework.

The immediate toll: excess mortality

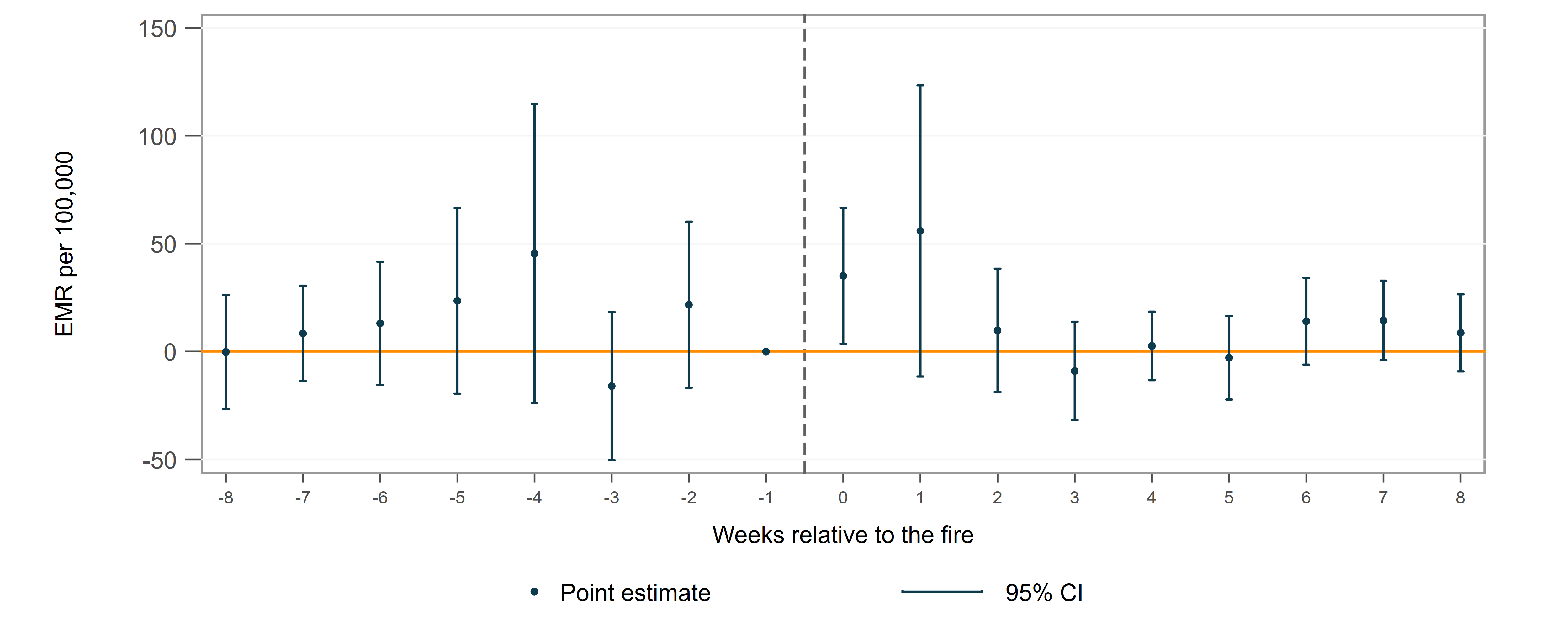

Our analysis using a difference-in-differences design indicates a sharp increase in mortality among children under the age of five during the week of the fire. Specifically, we find a 119% rise in excess mortality for smoke-affected children, relative to typical mortality rates at the time, shown in Figure 3. This stark increase underscores the severe health risks posed by wildfire smoke, even at distances far removed from the flames themselves.

Figure 3: Point estimates of the excess mortality rate of children under the age of five relative to the fire week using a difference-in-differences counterfactual design.

Long-term consequences: economic setbacks decades later

The later-life effects of the wildfire smoke were just as concerning. Our econometric results show that early childhood exposure to the smoke had lasting repercussions. Decades after the fire, men who had been exposed as young children experienced lower socioeconomic status compared to those who were not exposed. By 1930, these individuals ranked by 7-11% lower on composite socioeconomic measures combining occupation, education, and prestige. By 1940, they were earning approximately 4% less than their non-exposed peers.

Why does this matter?

Our research underscores a key insight: the impacts of wildfire smoke are not confined to the immediate aftermath of a fire. The consequences can ripple through time, affecting health, human capital, and economic well-being for decades. As climate change drives more frequent and severe wildfires, it is crucial to understand the full scope of these effects. While awareness of fire-sourced air pollution and mitigation strategies has improved since 1910, our study shows that smoke exposure carries risks beyond respiratory issues, with long-term socioeconomic consequences. Addressing these risks requires policies that not only focus on fire suppression but also prioritise public health, particularly for vulnerable communities with limited access to protective measures.

While the flames of the Great Fire of 1910 were extinguished over a century ago, its legacy continues to offer valuable lessons about the long-term consequences of wildfire smoke exposure. By better understanding these impacts, we can work toward more comprehensive strategies for mitigating the effects of modern-day wildfires on public health and well-being.

Leave a Reply